Jedidiah Gist-Anderson at Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church in Montgomery.

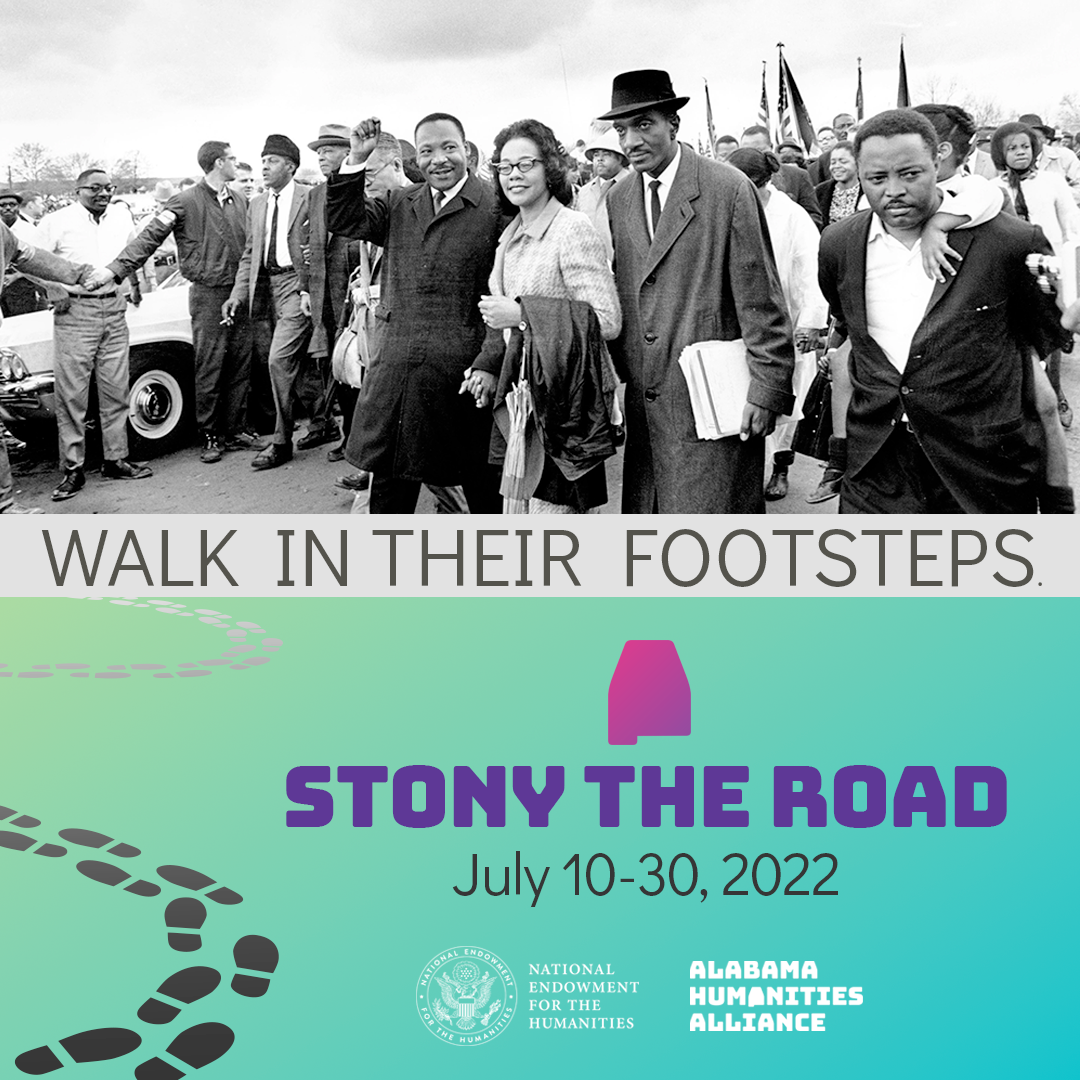

A North Carolina teacher reflects on “Stony the Road We Trod: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy." Read the full story below.

By Jedidiah Gist-Anderson

This summer, I had the gracious opportunity to participate in a teaching program through the Alabama Humanities Alliance and the National Endowment for the Humanities. “Stony the Road We Trod” helped me to see Alabama, its unsung heroes, and civil rights foot soldiers in a different light than ever before.

Over the course of this three-week institute, I had the honor to meet civil rights scholars, veterans of the movement, and individuals who were impacted by the movement. There are so many I could talk about, but I want to highlight at least a few moments that truly resonated with me during this experience.

I want to start with Rev. Carolyn McKinstry, who was present on September 15, 1963, when KKK members bombed Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four of Carolyn’s young friends. Her presentation resonated with me — not just because of her personal experience, but with how she took that experience and pursued a life of service and ministry. McKinstry’s message was authentic and sincere; it was a message of redemption and reconciliatory love. Her words reminded me that some church leaders in the movement believed that — even as they fought for their rights — they still tried to love those who ridiculed them, persecuted them, and despised them.

Mrs. Ruby Shuttlesworth Bester’s story about her father made me feel starstruck. I have taught African American Studies for 16 years and never did I ever hear about her father, the late Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth — and I was ashamed. However, just hearing her personal account of witnessing her father’s strength and courage firsthand, and to share that with us, was amazing.

I admired Mrs. Shuttlesworth Bester even before I met here after reading Andrew Manis’ book for the institute: A Fire You Can’t Put Out: The Civil Rights Life of Birmingham’s Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. He was a man beyond his years and his dogmatic tenacity invigorated me to fight for what you believe in and to stand on that even if you must stand alone.

Our cohort also had the chance to tour historic sites and museums around the state. That included learning from staff at the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Civil Rights Memorial Center and its Learning for Justice program, as well as the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Visiting those sites were the most riveting experiences I have ever encountered outside of visiting Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Israel that I visited when I was a teenager.

It’s one thing to see something so powerful a as the National Memorial for Peace and Justice on television. But to see and touch the names of Black lynching victims from across the country etched into those beams — it hit me to the core emotionally. The SPLC’s presentation about some of those lynchings unearthed some emotions I had not felt in such a long time. Compassion for the victims and their families for what happened to them. And shame and hurt thinking about how lynching was once a part of America’s national character.

This institute also gave me hope, though. For instance, despite all the injustices that have taken place in this nation, the EJI’s Legacy Museum tour ends with hope in a room it calls The Reflection Space. The room illuminates all the African Americans who have worked throughout their lives to make an impact and challenge racial injustice, even with obstacles facing them.

Back home now, one of the things that I am striving to do in my classroom is to never forget the unsung heroes of the civil rights movement, such as Selma’s JoAnne Bland; Freedom Rider and activist Bernard LaFayette; civil rights activist Viola Liuzzo; and civil rights attorney Arthur Shores. They fought to keep the soul of the civil rights movement going by any means necessary. Their authenticity and personal struggles, trials and victories, made me think: Where are our foot soldiers for today?

I will never forget this experience and I plan to spill all this newfound knowledge and information with my students so they can push it forward to the next generation, and so that we do not forget those who were the foot soldiers of the movement.

Jedidiah Gist-Anderson participated in the 2022 cohort of Stony the Road We Trod: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy. Gist-Anderson is a social studies teacher at Mallard Creek High School in Charlotte, North Carolina. He has taught for 16 years and focuses on topics such as civics literacy and African American history.

"Stony the Road We Trod: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy" is a National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute for K-12 schoolteachers, presented by the Alabama Humanities Alliance and Dr. Martha Bouyer.

Learn more