Jen Reidel (right) shares a reflection on her Stony the Road experience.

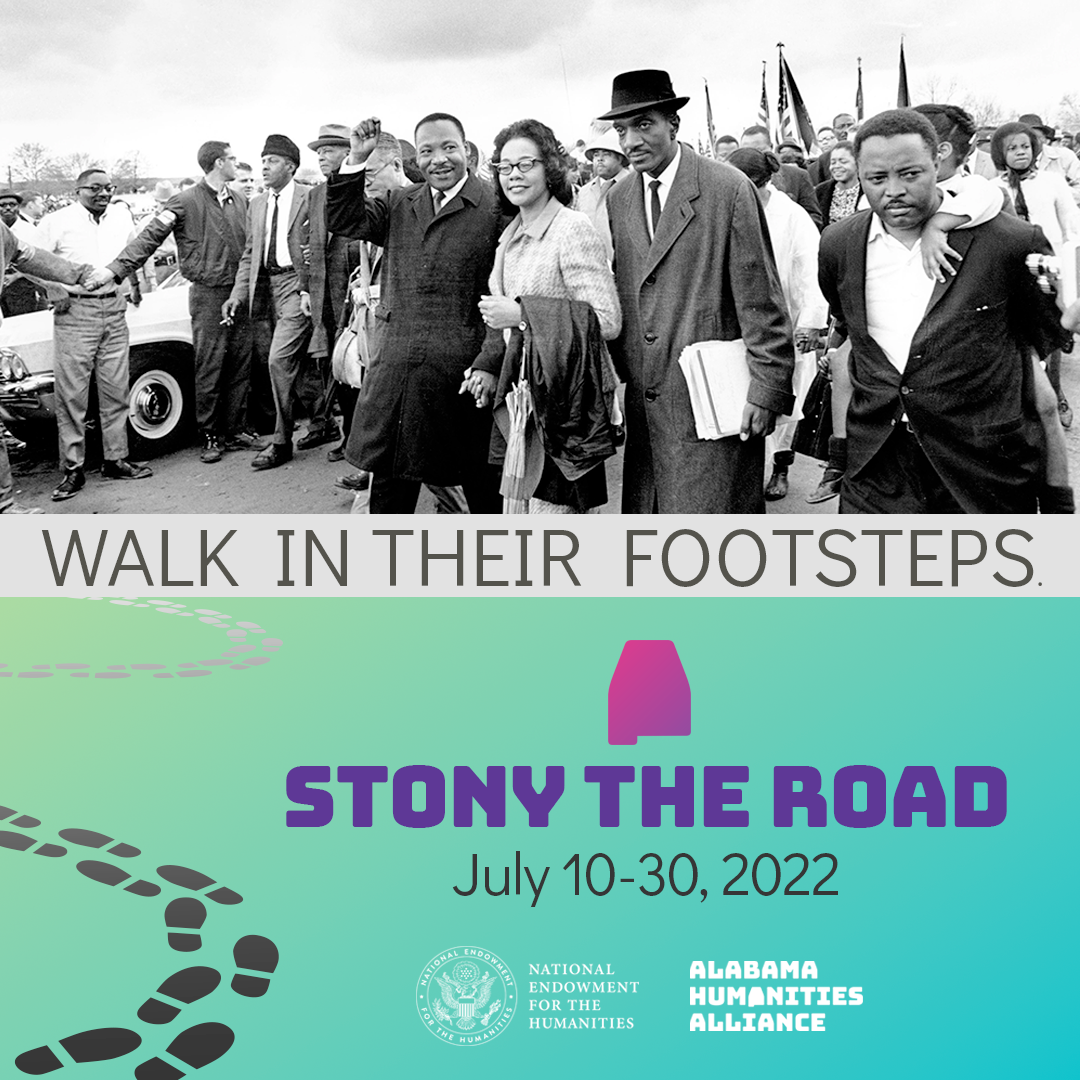

A Washington state teacher reflects on “Stony the Road We Trod: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy.” Read the full story below.

Reflection by Jen Reidel

Thanks to Dr. Bouyer’s passionate vision and leadership — along with the support of the Alabama Humanities Alliance and the National Endowment for the Humanities — 27 teachers from 17 states gave three weeks of their summer to come to Alabama. We came to learn about, deepen, and complicate our understanding of Alabama’s role in the civil rights movement, and to teach it accurately to our students. For me, and I suspect many others in our group, it was all that and much more.

Challenging history, resilience, hope, and transformation are how I would describe my experience as a participant in Stony the Road. Through visits to historic sites, presentations from civil rights scholars, and firsthand stories from those who bore witness to Alabama’s centrality in fight for equality for Black Americans, I gained a deeper and more complex perspective of the civil rights movement and its influence on America today.

As a teacher of U.S. history and civics, I thought I had a decent understanding of the movement; yet through this experience, I have a much broader and more sophisticated grasp of how important Alabama was in the fight for equality in the South and the nation at large. I am excited, as well as challenged, by how this experience will influence and inform my teaching.

On an academic level, the experience has pushed me to reframe my thinking and teaching of the civil rights movement to ensure I’m not perpetuating myths and distorting the realities of the movement. One of the most impacting academic sessions was with scholar Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Ph.D., who identified for us incorrect master narratives that distort the truth of history. He also taught us how to “disrupt” those fallacies with a more well-rounded teaching of civil rights narratives. An example of this is when teachers limit civil rights instruction to the American South. Dr. Jeffries pointed out in doing this it regionalizes white supremacy, distorts and confuses de jure and de facto segregation, and decontextualizes Northern protest. He encouraged us to “complicate the South, add into your teaching the Northern protests.”

Additionally, Dr. Jeffries urged us to abandon teaching a Dr. King-centric approach that suggests: “The movement is MLK, and we wind up running around looking for ‘little Kings.’” When the focus is on the pulpit instead of who was in the pews, students and other learners of history miss studying the richness of the movement and the efforts of the Black working class, the children, and the women who sacrificed for the cause.

Our site-based historical visits through Stony gave life and form to our academic sessions. For me, there are no words to fully describe feelings associated with walking the Edmund Pettus Bridge; worshipping inside the 16th Street Baptist Church; standing on the grounds where men with dogs and hoses attacked children who marched for equality in Kelly Ingram Park; sitting in the pews at Bethel Baptist Church; standing behind Dr. King’s pulpit at Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church; and walking the grounds of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, sometimes called the Lynching Memorial. I know without a doubt that my witness to history through these site visits will deeply impact my students.

Perhaps most transformative for me were the sessions where we listened to and talked with foot soldiers of the cause, daughters of leaders in the movement, and those who lived through this defining period in our nation’s history. For instance, activist and leader Bishop Calvin Woods shared with us about his experiences working within the Birmingham campaign and the sacrifices he made for freedom, including multiple arrests and time behind bars. He told us: “When you are fighting for real rights, there is no color line.”

Hearing the experiences of those in the movement makes this history all the more recent and relevant. Stories such as those from JoAnne Bland, a civil rights activist and an 11-year-old participant in Bloody Sunday in Selma back in 1965. Bland told us that, as a child, freedom for her meant being able to eat ice cream at Carter Drug Co.’s lunch counter in Selma. Similarly, for Janice Kelsey — a Children’s Crusade marcher in 1963 as a high school junior in Birmingham — freedom meant being able to eat at J.J. Newberry’s lunch counter or trying on shoes before buying them in a department store.

We also heard from Barbara Shores, daughter of civil rights attorney Arthur Shores, and Ruby Shuttlesworth Bester, daughter of civil rights leader Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, who each spoke about the sacrifices that entire families in the movement made in the fight for equality. Both women shared how it affected them to survive having their homes bombed multiple times by white supremacists, and they revealed the trauma created by those events. Mrs. Shuttlesworth Bester described her family’s sacrifice this way: “Our struggle was one of love, we did what Daddy (Rev. Shuttleworth) asked us to do.” These stories and many others from those who participated in and witnessed history will be invaluable as I teach about civil rights.

I will forever be grateful for the opportunity to confront history in person — up close and alongside some of the finest educators I have met.

History matters and knowing it in its fullness is powerful and transformative.

As civil rights historian and author Glenn Eskew shared with us: “The story (of civil rights in Alabama) is about justice, reconciliation, and changing the world for the better.”

Our students deserve to know the past in all its truth, how it informs the present, and be encouraged by ordinary people who did the extraordinary in their fight for equality. The march continues…

Jen Reidel participated in the 2022 cohort of Stony the Road We Trod: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy. Reidel has served as a teacher for 26 years. She currently teaches civics and U.S. history in the Bellingham School District at Bellingham High School, in Washington.

"Stony the Road We Trod: Exploring Alabama’s Civil Rights Legacy" is a National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute for K-12 schoolteachers, presented by the Alabama Humanities Alliance and Dr. Martha Bouyer.

Learn more